[Panel from "Pasha Noise," by Brian Kim Stefans and Gary Sullivan.]

David Larsen, from "On Melodrama":

When the emotions expressed by a person are in excess of what a given situation appears to call for, that person is vulnerable to the charge of MELODRAMA. MELODRAMA is useful for dismissing a companion's reactions to a situation when these are inconvenient or unwelcome, suggesting as it does the bad faith of the theater and the overthrow of the companion's authentic behavior by some hackneyed cybernetic script. Its coercive force is transparent: MELODRAMA represents the accused as overstepping the bounds of whatever role the accuser has deemed him or her fit to play, and seeks to shame the accused into a more muted performance. "Don't act this way," act THAT way. Know your role. Stop crying."

To acquit oneself of the accusation of MELODRAMA is difficult. It obliges the accused to account for the expressive activity whcih has so displeased the accuser, and to demonstrate its proportionality to the situation at hand. Such a demonstration may involve complex information the accuser is unwilling to consider or unequipped to comprehend. In any case, the accused is rarely given the opportunity for self-vindication: MELODRAMA indicates that the accuser has small regard for the accused's experience of the situation, and already prefers mere BAD ACTING to whatever explanation the accused might give.

David recuperates the term "melodrama" from its pejorative connotations. We're ashamed to be thought of, seen as "melodramatic," which is a kind of admittance of inappropriate public display of emotionality. This prohibition is deeply etched into the social code, and I suspect it's one of the barriers that has kept most us from any real experience with the world's most productive, varied, and inspiring entertainment factories: Bollywood.

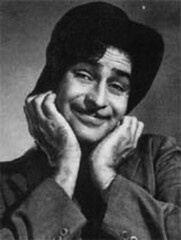

Indian popular cinema, like our own, is largely melodrama, but unlike ours it's undisguised, unashamed to be melodramatic, is often almost Brechtian in its self-awareness, except that the major foreign influences--at least on the golden age directors of the 50s--were the seemingly incompatible Cecile B. de Mille, Busby Berkeley, and Vittorio di Sica.

Raj Kapoor, the most popular director of Hindi cinema in the 50s, was affectionately known as "the great entertainer," and at his best was able to move fluidly in a single film from the stark realism of di Sica, the highly stylized song-and-dance numbers of Berkeley, the epic scale of de Mille, and the comedy of Chaplin, who Kapoor was often, for obvious reasons, compared with. Awaara, which Kapoor directed in 1951, remains one of the finest films anyone has ever made. We're going to watch the 9-minute-long dream sequence, which took three months to shoot, and which is as moving as it is beautiful as it is melodramatic as it is kitschy as it is surreal.

Singing master Giovanni Battista Lamperti wrote: “There is force inside your primal nature like that which ‘moves mountains.’”

Melodrama, radically speaking, is melos – music plus drama -- a double whammy. If we have come to use the term pejoratively, as LRSN mentioned in his poem-essay, it could be because we are afraid of the power of the combination. I can’t hear the word melodrama without thinking of the word “full-throated,” and I can’t hear “full-throated” without starting to muse on divas.

The term “diva” is often used pejoratively as well, when it is not used campily, as when referring to a man, or cutesy-petulantly, as on a tight pink t-shirt marketed to urban teens. But a true diva is like a fifth wind, an elemental force, at once complexly controlled and terrifyingly unrestrained.

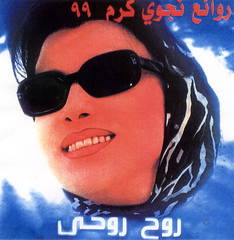

The throat of Lebanese Christian diva Najwa Karam is truly a channel of wonder and her life was in many ways melodramatic. Successful early in her career, she was later plagued by scandals, including eloping at 4:00 a.m. one night with Yosef Harb, a Muslim music promoter living in Canada, who was several years her junior, and--much worse--being accused in Alkefah Al-Arabi of having told a television interviewer that she had named a pet dog after the prophet Mohammed.

After the article appeared, Karam filed a lawsuit, and assumed--as she didn't even own a pet--the matter would quickly be forgotten.

By early 1999, however, morally incensed busybodies were frantically faxing the story to magazines and radio stations throughout the Arabic world. According to a report in a March 1999 issue of Al-Ahram Weekly, Riyad Daoud, a former member of the Jordanian parliament, publicly called for Karam's death. She was banned from entering Jordan and Qatar.

The melodrama of the life, though, is dwarfed by the (full-throatedly non-pejorative!) melodrama of the voice. Here’s an excerpt from "Baladeeat":

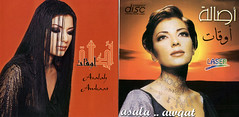

Asala Nasri may not have had quite the melodramatic life of Najwa Karam, but this Syrian-born singer, daughter of one of the most important 20th century composers in the country, is one of few contemporaries whose expressive voice can give Najwa a run for her money.

The two images above, by the way, are of two versions of Asala's latest CD, Awqaat. The one on the left is the version available in Tower Records, the one on the right is the one for sale in all of the Arabic music places in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. The biases here are not uncommon: selling an Orientalized Asala to the west, and an Occidentalized Asala to the east.

This is "Khalik Hena," from her 2004 live album, "A Night at the Opera," a song earlier made popular by Warda. This is one of few instances I know of where a singer wrings the maximum amount of expressive force from a passage by keeping her mouth closed tightly as she sings ...

[Gary's note: I was unable to find that particular recording online, but here she is singing "Khalik Hena" at another concert. Alas, it appears to begin just at the end of what would have been the mouth-mostly-closed section of the song.]

We can’t speak of autre divas without mentioning, if only in passing, enka singer Misora Hibari. Misora Hibari is a Japanese national treasure. In Arashiyama, in Kyoto, you can visit the Misora Hibari museum, where you can see her old album covers, her shoe and handbag collection, and a three-screen projection of one of her schmalziest videos, Kawa no nagare no yo ni.

Many years ago in Tokyo, I [Nada] was trying to learn enka, and even auditioned for a TV show featuring foreigners singing enka. I didn’t pass, but I met a woman named Chris Chavez who was obsessed with Hibari to the point of learning all of her songs note-for-note, and impersonating her on TV.

Here’s the original version of the song I heard Chris Chavez sing in Tokyo: Kuruma-ya-san. Notice how it weaves back and forth between eastern and western.

[Gary's note: Unable to find the original version, but here she is singing it live:]

Haitian poet Michel-Rolph Trouillot writes: "Haitian Creole, the only language shared by all Haitians, took—and continues to take—most of its vocabulary from French. Yet in many ways, its syntax is closer to various African languages than to French. Is Haitian an African or a Romance language? The correct answer is that Haitian language subverts the very categories from which it stems."

Haitian Creole literature is relatively new, beginning in 1953 with the publication of Feliks Moriso-Lewa's Diacoute.

Haitian poetry tends to be fairly politicized, with an often anthemic quality. Joj Kastra's poems are melodramatic in the full, or "radical," sense: Listen to the musicality of "San":

An n'al gade san koule,

cheri

pou yon fwa nan lavi,

se pa san moun k'ap koule,

pou yon fwa nan lari

se pa san bet k'ap koule,

cheri

se soley ki pral kouche.

Dambudzo Marechera, born in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, wrote in English: "For a black writer," he said, "the language is very racist; you have to have harrowing fights and hair-raising panga duels with the language before you can make it do all that you want it to do."

Marechera was involved in student protests against racial discrimination at the University of Rhodesia, and reportedly marched--by himself--in protest of the government of Ian Smith. He was forced to leave the country for Botswana and then to England, where he studied English literature, hung out with Rastafarians, and wrote stories and poems, for what he called a "tarmac audience." Presumably, he meant an audience of no particular fixed place.

In the mid-80s Marechera returned to Zimbabwe, where he lived in friend's living rooms and on the street, and wrote the plays, poems, stories and journal entries that made up the last book published while he was still alive, Mindblast:

It's Disco Time at Scamps and Chantelles

You and I in platform boots and imitation Levis

Will mimic the hours in twirl and stomp

The likes of Gary Glitter;

Icecream hats and Rasta T-Shirts the emblems

Of our liberation's arrival--Guitars, trombones,

Ukeleles, harps, synthesizers, instruments of wind and air,

I think of Stravinsky (Soldier's Return)

And hibuscus/violets in the shadow of Great Zimbabwe.

smm panel

ReplyDeletesmm panel

iş ilanları blog

İNSTAGRAM TAKİPÇİ SATIN AL

hirdavatciburada.com

beyazesyateknikservisi.com.tr

SERVİS

tiktok jeton hilesi

learn the facts here now s6m28c9j47 replica louis vuitton replica bags wholesale india replica bags koh samui click to read more y1i99g7e77 replica bags thailand replica bags near me go to website i8y04s6u01 replica bags india

ReplyDelete