[Panel from "Pasha Noise" by Brian Kim Stefans and Gary Sullivan.]

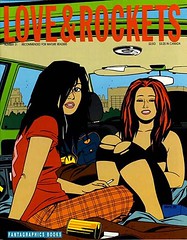

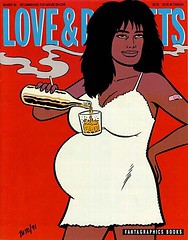

This brings us very nicely to Reverb. In the U.S., few contemporary artists embody the concept of intercultural reverb more than Mario, Gilbert, and Jaime Hernandez aka Los Bros Hernandez, the team behind Love and Rockets ...

perhaps the most successful indy comic book series of the 1980s. Which was a surprise to Mario, Gilbert, and Jaime, who almost didn't bother submitting their work when they started out. Who among regular readers of comics, they worried, would be interested in Jaime's stories of southern Californian Latinos

or Gilbert's stories centered in Palomar,

a fictional small town somewhere in Central America? To make matters more complicated, most of the, in both cases, huge casts of characters, consisted of almost exaggeratedly strong women,

many of whom, like some of their male counterparts, were bisexual. Add in a group of she-male strippers and a lot of cultural references--like figures from Mexican wrestling

or outre comics that mean nothing to most comics readers in the USA--and you can see why the Hernandez brothers were surprised to one day find themselves among the most influential comics creators of the 1980s and 90s.

In the context of The Autré, the term “reverb” not only signifies intercultural reverberations but cultural misprisions and inappropriacies (which Word informs us is not a word).

The 1977 Bollywood film, "Amar Akbar Anthony," directed by Manmohan Desai, is the tale of siblings separated in early childhood who are raised in three different families: one Hindu (Amar), one Muslim (Akbar), and one Catholic (Anthony). The plot, like those of so many Bollywood films, is too complex to recount here, but for our purposes, it’s useful to note that the film is set in the former Portuguese colony of Goa. Anthony, the Catholic, is played by Amitabh Bacchan, who is without question the most famous film star in the world, although many Americans have never heard of him. Watch as he, a Hindu in Bombay playing a Catholic in Goa impersonating a dandified posh Englishman, turns both colonialism and language on their heads:

Russian Futurist Alexei Kruchenykh was part of the scene that included Khlebnikov and Mayakovsky, but his work was so far out, he has since been all but forgotten. Contemporary Russian poets--according to Kruchenykh's translator, Jack Hirschman--think of him, if at all, as simply a failure, a model to be avoided at all costs.

Hirschman, however, provides a nearly 300-page glimpse into the still vibrant life-work of Kruchenyhkh, which reads more like something written today than anything recent I've personally read from Russia:

TOPSYTURVY DEATH

My glandule pined for a tartlik a salad

and knockwoodmen of cock-and-bull stories

and throwing over an inflammable hut

I rise up as a starchy songstress!

I've given memory up for a thirst for the new:

the smoke and hiss of a tubercular machine

a black man stoker dancing jacketlessly

naked ... hail! Turpentine!

I'M ARMATURING! SHACKLED WITH DANCYARMOR

soaring over the abyss like eddies of nautical bubblings,

AND SWOONING GIRLS ARE CHEWED TO THE BONE

AS CONSEQUENCES OF BEAUTY!

and everybody's gathered here

fidgetty with juts of flesh

kneeing me down to the ground

softly shooting into my brow

kiz! zing!

a futuristiff!

Kruchenykh, by the way, is one of the first poets outside of the U.S. to have publicly acknowledged being inspired in part by American jazz--in 1930.

Let's turn to Sean Golden and Chu Chiyu's translations of Gu Cheng, the most outrageous poet of the so-called Misty school of contemporary Chinese poetry. Whereas most of the Misty school gained notoriety largely for breaking from a long-standing tradition in Chinese poetry of infinite echoing back through the Chinese canon, Gu Cheng went even further, in the creation of a poetry that, according to his translators:

"comes out of an attempt to recover the original childlike relationship with the words of a language one does not yet know. The poems are not an imitation of Gertrude Stein (whose work did, however, influence some of the translations) or a putting into practice of postmodern concepts of the tyranny of language and the need to break it down. This fact illustrates the futility of attempting to judge contemporary Chinese writing by purely Western standards."

Here's a bit of "Deedledeedee" from the longpoem Quicksilver:

At first you were happy to pass on

clapping hands

walking through the grasslands

leaves burst forth from the trees

words spring forth from your lips

leaves

you linger, start up the machine,

springing forth plunging into the mists

upturned bucket seen from afar

droplet

so many tiny slivers of fish

twisting in the air

deedledeedee

fish carry the trees up into the air

droplet

fish carry the trees up into

air

brown trunks upright in the

air

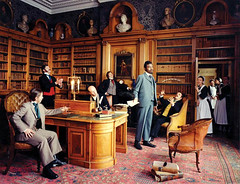

Like the Japanese artist Yasumasa Morimura, who is a kind of male Japanese Cindy Sherman, British-born Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare

inserts himself into his work in the guise of ironic personae – here he is a 19th Century dandy in a flawless tableau. He also has made ingenious use of textiles to create gorgeous objects that reverberate with the history of cultural imposition.

He uses Dutch wax prints, a kind of textile which ironically is neither exclusively Dutch (the British made them, too), nor wax (the process actually uses resin), nor, technically, a print. The Dutch concocted them with the intention of undercutting the Indonesian textile business, but were unable to sell them to the Indonesians, whose batik fabrics were far more refined. The colonists then marketed the fabrics, with their characteristic veining and spotting, to the Cote d'Ivoire, where they became so popular that we now think of them as African prints. Here on the headless white mannequins, made up into the clothes of the colonizers, they look at once vivacious and culturally wrong.

Shonibare’s 3-D re-vision of “The Swing,” the already-outrageous rococo painting by Jean-Honore Fragonard, is an autré delight to behold.

I really like this.

ReplyDeleteI dislike a lot of discussions of "community" in contemporary American poetry - this idea that we can somehow not be alienated from each other. And with it, the demonization of "the exotic." As if there was this positivist truthful way of approaching other cultures (itself a very 19th century idea).

Just a brief note: the Dadaists saw "jazz" as more or less synonymous with Dada - thus Richard Huelsenbeck's "jazz" drumming while reading his Fantastic Prayers. Jed Rasula has a whole book in the process on "jazzbandism." Part of it was published in the Georgia Review a few years ago.

Johannes

replica bags nyc replica bags philippines wholesale 7a replica bags wholesale

ReplyDelete